Arooj Fatima 3106-FLL/BSENG/F22, Ayesha Iftikhar 3157-FLL/BSENG/F22, and Momina Rauf 3163-FLL/BSENG/F22

Department of English, International Islamic University Islamabad

ENG 404: Applied Linguistics

Ma’am Kaukab Saba

December 16, 2025

Abstract

This study investigates communicative competence development among university ESL learners from a sociocultural perspective, emphasizing language learning as a socially mediated process shaped by interaction and scaffolding. Grounded in Sociocultural Theory, the research examines how teacher-mediated, peer-mediated, and AI-mediated scaffolding operate within learners’ Zones of Proximal Development. Addressing gaps in existing literature, the study explores the integrated role of multiple mediational agents rather than examining them in isolation. A mixed-method comparative design was employed, involving a traditional classroom group and an AI-assisted group, using pre- and post-speaking assessments, classroom observations, and AI interaction logs. Quantitative findings reveal significantly greater communicative gains in the AI-assisted setting, while qualitative data highlight increased fluency, confidence, and learner autonomy. The results demonstrate that AI-mediated scaffolding enhances the frequency and continuity of guided practice while complementing, rather than replacing, teacher and peer support. The study contributes theoretically by extending Sociocultural Theory to technology-enhanced contexts and pedagogically by informing balanced instructional models that integrate human and artificial mediation to support communicative competence in higher education ESL classrooms.

Keywords: Ai-assisted learning, collaborative learning, communicative competence, mediation. scaffolding, sociocultural theory (SCT) and virtual reality (VR).

Introduction

Language learning in higher education is increasingly understood as a socially mediated process rather than a purely cognitive activity based on memorization and repetition. Contemporary applied linguistics research emphasizes that communicative competence develops through interaction, mediation, and collaborative engagement, where learners actively construct meaning with others (Vygotsky, 1978; Lantolf & Thorne, 2006; Swain, 2000). From this sociocultural perspective, language is not only a medium of communication but also a primary tool for cognitive development.

Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory (SCT) provides a strong theoretical foundation for understanding second language acquisition as a process that first occurs at the social level and is later internalized by learners (Vygotsky, 1978). In this framework, learning is facilitated through scaffolding, which is provided by teachers, peers, and mediational tools within the learner’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). Research consistently shows that guided interaction plays a crucial role in developing communicative competence, particularly in higher education ESL contexts (Swain et al., 2011; Wong & Larkin, 2020).

In recent years, the expansion of digital technologies has significantly reshaped university language classrooms. Artificial Intelligence (AI), automated feedback systems, and Virtual Reality (VR) environments now offer learners continuous access to language input, practice opportunities, and immediate feedback (Warschauer, 1996; Kern, 2014; Zhang & Zou, 2022). These tools introduce new forms of mediation that extend scaffolding beyond classroom time and physical interaction. AI-powered chatbots, for example, allow learners to engage in sustained conversational practice without time pressure, while automated feedback systems support accuracy and fluency development through immediate corrective input (Lee, 2023; Liu et al., 2024).

Despite the growing use of AI in language education, important pedagogical and theoretical concerns remain unresolved. A central question is whether AI can function as a legitimate mediational artifact within the sociocultural framework or whether it risks diminishing the human and social dimensions of language learning. While some argue that AI may replace traditional teaching roles, others emphasize that it should complement teacher and peer scaffolding rather than substitute them (Zhao, 2020; Zhang & Zou, 2022). This study addresses this debate by examining the combined roles of teacher-mediated, peer-mediated, and AI-mediated scaffolding in developing communicative competence among university ESL learners.

Background of Study

The teaching of second language communication at the university level has undergone substantial transformation due to rapid advancements in educational technology. Traditional language classrooms, which relied heavily on teacher-centered instruction and limited interactional opportunities, are now supplemented by digital platforms that support autonomous learning and continuous practice (Warschauer, 1996; Kern, 2014). However, many university ESL classrooms still face persistent challenges such as large class sizes, restricted instructional time, and learner anxiety, which limit individualized scaffolding and meaningful interaction.

Although communicative language teaching (CLT) promotes interaction and learner participation, its implementation in higher education contexts is often constrained by institutional and logistical factors. Teachers may struggle to provide consistent, individualized feedback, and peer interaction varies in quality depending on learners’ confidence and proficiency levels (Dörnyei, 2009; Wong & Larkin, 2020). As a result, not all learners receive adequate opportunities to operate within their ZPD during classroom activities.

The emergence of AI and VR technologies offers new possibilities for addressing these limitations. AI-based chatbots enable learners to engage in repeated, low-anxiety conversational practice, while automated feedback systems provide immediate responses to linguistic errors (Lee, 2023). VR platforms further enhance learning by placing learners in simulated communicative contexts that resemble real-life academic and social situations, thereby promoting confidence and communicative engagement (Chen, 2022; Hua & Wang, 2023).

From a sociocultural perspective, these technologies can be viewed as mediational artifacts that shape learning activity and support internalization processes (Vygotsky, 1978; Lantolf & Thorne, 2006). However, learners in real university settings rarely rely on a single source of mediation. Instead, they navigate multiple layers of scaffolding, including teacher guidance, peer collaboration, and technology-mediated support. Despite this reality, existing research tends to examine these mediational sources in isolation, creating a gap in understanding how they interact within a unified learning environment.

This study is positioned within this gap and seeks to explore how teacher, peer, and AI-mediated scaffolding operate together in traditional and AI-assisted university ESL classrooms. By adopting a sociocultural lens, the research aims to provide a more integrated understanding of mediated interaction and communicative development in contemporary higher education contexts.

Research Objectives and Research Questions

The primary objective of this study is to examine the contributions of teacher-mediated, peer-mediated, and AI-mediated scaffolding to the development of communicative competence among university-level ESL learners. The study aims to provide insight into how different mediational agents support learners during communicative tasks and how these forms of scaffolding interact in both traditional and AI-assisted learning environments (Vygotsky, 1978; Swain et al., 2011).

Specifically, the study seeks to:

- Explore the roles of teachers, peers, and AI tools in scaffolding learners’ communicative performance

- Compare the frequency and effectiveness of scaffolding strategies in traditional and AI-assisted classrooms

- Examine the role of collaborative interaction in enhancing communicative competence across both settings

Based on these objectives, the study addresses the following research questions:

- What roles do teachers, peers, and AI tools play in scaffolding learners’ communicative competence in university ESL classrooms?

- Which scaffolding strategies are most frequent and effective in traditional and AI-assisted learning environments?

- How does collaborative interaction influence learners’ communicative performance in both instructional contexts?

Significance of Study

This study holds substantial theoretical, pedagogical, and empirical significance within the field of applied linguistics and second language education, particularly in the context of higher education ESL instruction. At the theoretical level, the research reinforces the continued relevance of Sociocultural Theory (SCT) in contemporary, technology-enhanced learning environments. By examining teacher-mediated, peer-mediated, and AI-mediated scaffolding within a single framework, the study demonstrates that core sociocultural concepts such as mediation, scaffolding, and the Zone of Proximal Development remain applicable even when digital tools are integrated into language learning (Vygotsky, 1978; Lantolf & Thorne, 2006; Swain et al., 2011). The findings extend sociocultural perspectives by illustrating how AI tools can function as mediational artifacts that complement, rather than replace, human interaction.

From a pedagogical perspective, the study provides practical insights for university-level language instructors and curriculum designers who seek to integrate AI tools into communicative language teaching. The research highlights how AI-mediated scaffolding can address common classroom challenges such as limited instructional time, large class sizes, and unequal participation by offering learners continuous, individualized feedback beyond classroom constraints (Warschauer, 1996; Kern, 2014; Lee, 2023). At the same time, it underscores the continued importance of teacher guidance and peer collaboration in supporting affective needs, contextual understanding, and meaningful interaction (Donato, 1994; Wong & Larkin, 2020; O’Reilly & Whelan, 2021). These insights can inform balanced instructional models that combine human and technological mediation to enhance communicative competence.

Empirically, the study contributes comparative evidence on the interaction of multiple sources of scaffolding in traditional and AI-assisted university ESL classrooms. By analyzing how teacher, peers, and AI-mediated support operate together, the research fills a gap in existing literature that often examines these forms of mediation in isolation (Zhang & Zou, 2022; Liu et al., 2024). The findings offer data-driven guidance for future curriculum development, instructional planning, and technology adoption in higher education language programs, particularly in contexts where access to resources and learner needs may vary. Overall, the study provides a nuanced understanding of how integrated scaffolding practices can foster communicative competence while preserving the social foundations of language learning. Peer collaboration enabled learners to co-construct meaning, share linguistic resources, and reduce anxiety during speaking tasks. In the AI-assisted setting, collaborative interaction was further enriched by reflective discussions on AI-generated feedback. This integration of social and technological mediation aligns with SCT’s emphasis on learning as a socially embedded process and underscores the importance of maintaining collaborative practices in digitally enhanced classrooms.

Literature Review

Research in applied linguistics consistently highlights that the development of communicative competence is a socially mediated process shaped by interaction, guidance, and contextual support rather than isolated cognitive effort. Sociocultural perspectives emphasize that language learning emerges through participation in communicative activities where learners receive assistance from more knowledgeable others and gradually internalize linguistic forms and functions (Vygotsky, 1978; Lantolf & Thorne, 2006). Within this framework, scaffolding plays a central role in enabling learners to perform beyond their current level of independent ability.

Teacher-mediated scaffolding has long been recognized as a fundamental component of effective second language instruction. Teachers provide structured support through modeling, questioning, reformulation, prompts, and corrective feedback, all of which guide learners toward more accurate and fluent language use (Donato, 1994; Wong & Larkin, 2020). Such mediation is particularly important in communicative tasks, where learners often struggle with fluency, coherence, and pragmatic appropriateness.

Studies indicate that effective teacher scaffolding is contingent and adaptive, responding to learners’ immediate needs rather than following rigid instructional patterns (Al-Sobhi, 2020). Through dialogic interaction, teachers help learners notice linguistic gaps, negotiate meaning, and refine their communicative output. In university ESL contexts, teacher mediation also provides affective support by reducing anxiety and fostering a classroom environment conducive to risk-taking and participation (Dörnyei, 2009). However, despite its effectiveness, teacher-mediated scaffolding is often constrained by limited class time, large student numbers, and institutional demands, which restrict opportunities for individualized support.

Peer-mediated scaffolding has gained increasing attention as a valuable complement to teacher support in communicative language learning. From a sociocultural perspective, learners can collaboratively construct knowledge by sharing linguistic resources, negotiating meaning, and co-producing language during interaction (Donato, 1994). Peer collaboration enables learners to function within shared Zones of Proximal Development, where mutual assistance supports communicative development.

Empirical studies demonstrate that peer interaction enhances fluency, lexical development, and interactional competence, particularly during group discussions and task-based activities (O’Reilly & Whelan, 2021). Peer scaffolding also encourages learner autonomy and responsibility, as students actively participate in managing their own learning processes. However, the effectiveness of peer mediation can vary depending on learners’ proficiency levels, confidence, and willingness to collaborate. Without appropriate guidance, peer interaction may remain superficial or unevenly distributed, limiting its potential benefits (Wong & Larkin, 2020).

With the advancement of educational technology, AI-mediated scaffolding has emerged as a significant area of interest in second language education. AI tools such as chatbots, automated feedback systems, and intelligent tutoring platforms provide immediate, consistent, and personalized feedback that supports learners’ linguistic accuracy and fluency (Lee, 2023; Liu et al., 2024). These tools allow learners to engage in repeated practice without fear of negative evaluation, which is particularly beneficial for developing speaking skills.

Research suggests that AI-mediated environments reduce learner anxiety and increase opportunities for autonomous practice, especially outside classroom settings (Zhao, 2020). Automated feedback enables learners to notice and correct errors in real time, facilitating gradual movement toward self-regulation. Additionally, Virtual Reality (VR) platforms simulate authentic communicative situations, promoting confidence and pragmatic competence by immersing learners in realistic interactional contexts (Chen, 2022; Hua & Wang, 2023).

Despite these advantages, scholars caution that AI-mediated scaffolding should not be viewed as a replacement for human interaction. While AI tools excel at providing form-focused feedback and extended practice, they lack the nuanced socio-emotional and contextual understanding offered by teachers and peers (Zhang & Zou, 2022). As a result, the effectiveness of AI in language learning depends largely on how it is integrated with existing pedagogical practices.

Although substantial research exists on teacher-mediated, peer-mediated, and AI-mediated scaffolding individually, relatively few studies examine their combined role within a single instructional context. Sociocultural theory emphasizes that learning is shaped by multiple mediational agents operating simultaneously, suggesting that communicative development is best supported through an integrated scaffolding model (Vygotsky, 1978; Swain et al., 2011).

Recent studies argue that AI tools are most effective when used to supplement teacher and peer interaction rather than replace them (Zhang & Zou, 2022; Liu et al., 2024). Teacher guidance remains essential for interpreting feedback, contextualizing language use, and addressing affective factors, while peer collaboration supports negotiation of meaning and shared understanding. AI-mediated scaffolding extends these processes by increasing the frequency and accessibility of practice opportunities beyond classroom constraints.

| Study / Theory | Type of Mediation | Context | Key Findings | Contribution to Communicative Competence |

| Vygotsky (Sociocultural Theory) | Social interaction and mediation | General learning context | Learning occurs through guided participation; language is a tool for cognition | Interaction enables internalization of linguistic structures and meanings |

| Wong & Larkin (2020) | Teacher-mediated scaffolding | Communicative classrooms | Systematic questioning, modeling, and recasting enhance learner interaction | Contingent teacher support improves participation and communicative accuracy |

| Al-Sobhi (2020) | Student / peer scaffolding | Classroom speaking activities | Peer support increases motivation, confidence, and speech development | Reduced anxiety encourages risk-taking in speaking |

| Donato (1994) | Collective scaffolding | Peer collaboration | Learners co-construct meaning by sharing linguistic resources | Collaborative interaction supports learning within the Zone of Proximal Development |

| O’Reilly & Whelan (2021) | Peer-mediated interaction | Online learning environment | Peer collaboration improves fluency, negotiation skills, and learner control | Regular peer interaction strengthens L2 speaking competence |

| Lee (2023) | AI-mediated scaffolding | Chatbot-assisted learning | AI feedback improves grammar accuracy, vocabulary use, and confidence | Immediate feedback supports autonomous speaking practice |

| Liu, Zhang, & Chen (2024) | Intelligent tutoring systems | AI-supported instruction | AI systems replicate teacher scaffolding features (contingency, fading) | Enhanced self-regulation and faster internalization of language structures |

| Chen (2022) | VR-mediated interaction | Virtual reality environments | VR immersion improves communicative competence in real-life simulations | Authentic social interaction boosts spontaneous language use |

| Hua & Wang (2023) | VR and AI-assisted learning | Immersive digital settings | VR reduces anxiety and increases social presence | Increased confidence and interactional competence |

This study builds on existing literature by examining how teacher-, peer-, and AI-mediated scaffolding interact within traditional and AI-assisted university ESL classrooms. By adopting an integrated sociocultural perspective, the research seeks to address a gap in current scholarship and provide a more comprehensive understanding of how multiple forms of mediation collectively support communicative competence

Research Methodology

This study employed a mixed-method exploratory research design to investigate the role of teacher-mediated, peer-mediated, and AI-mediated scaffolding in the development of communicative competence among university ESL learners. A mixed-method approach was selected because it allows researchers to capture both measurable learning outcomes and the interactional processes through which language development occurs (Creswell, 2014; Dörnyei, 2007). Such an approach is particularly suitable for sociocultural oriented research, which emphasizes the integration of quantitative performance data with qualitative evidence of mediated interaction (Lantolf & Thorne, 2006; Swain et al., 2011).

The study followed a comparative instructional design, examining two learning contexts: a traditional ESL classroom and an AI-assisted ESL classroom. Both groups were taught using the same syllabus, learning objectives, instructional materials, and assessment criteria to maintain pedagogical consistency (Warschauer, 1996; Kern, 2014). The primary distinction between the two contexts lay in the presence of AI-mediated scaffolding in the AI-assisted group, which was introduced as supplementary support rather than as a replacement for classroom instruction (Zhao, 2020; Zhang & Zou, 2022).

This comparative design enabled the study to explore how different sources of mediation—teachers, peers, and AI tools—operate within similar instructional conditions and contribute to communicative development (Vygotsky, 1978; Swain et al., 2011).

The participants comprised forty undergraduate ESL learners enrolled in a compulsory English communication course at a public-sector university. All participants were non-native speakers of English and ranged in age from eighteen to twenty-two years, which is consistent with typical university ESL populations examined in prior research (Dörnyei, 2009; Wong & Larkin, 2020).

Participants were randomly assigned to two groups: a traditional classroom group and an AI-assisted group, each consisting of twenty learners. Random assignment was used to reduce selection bias and enhance group comparability (Creswell, 2014). Both groups were instructed by the same teacher, which helped control for instructional variation and ensured that differences in outcomes could be more reliably attributed to the nature of scaffolding rather than teaching style (Al-Sobhi, 2020).

Instruction in the traditional classroom group was conducted through face-to-face communicative language teaching practices, including guided discussions, role plays, pair and group work, and oral presentations. Scaffolding in this setting was primarily provided through teacher modeling, prompts, clarification requests, recasts, and explicit feedback, as well as peer support during collaborative activities (Donato, 1994; Wong & Larkin, 2020; Swain et al., 2011).

The AI-assisted group participated in the same classroom activities as the traditional group but additionally engaged with AI-based tools outside classroom hours. These tools included an AI chatbot for conversational practice, automated systems for grammar and pronunciation feedback, and a Virtual Reality (VR) platform that simulated academic and everyday communicative situations. Previous studies suggest that such tools enhance opportunities for repeated practice, reduce anxiety, and support learner autonomy by providing immediate and individualized feedback (Zhao, 2020; Lee, 2023; Liu et al., 2024). In line with sociocultural principles, AI tools were used as mediational artifacts that complemented teacher and peer interaction rather than replacing them (Vygotsky, 1978; Lantolf & Thorne, 2006).

Multiple data collection instruments were employed to capture both learning outcomes and interactional dynamics. Pre- and post-speaking assessments were administered to measure changes in learners’ communicative competence over the course of the study. These assessments evaluated fluency, grammatical accuracy, lexical range, coherence, and interactional competence, which are widely recognized components of communicative ability in SLA research (Canale & Swain, 1980; Swain et al., 2011).

In addition, classroom observation checklists were used to document instances of teacher-mediated and peer-mediated scaffolding during instructional activities. Observational data are particularly valuable for examining how mediation unfolds in real-time interaction (Donato, 1994; O’Reilly & Whelan, 2021). For the AI-assisted group, AI interaction logs were analyzed to examine learner engagement patterns and the nature of feedback provided by AI tools, as recommended in recent technology-mediated language learning research (Lee, 2023; Liu et al., 2024). The use of multiple instruments allowed data triangulation, thereby enhancing the credibility of the findings (Creswell, 2014).

Quantitative data from the speaking assessments were analyzed to compare pre- and post-test performance within and across the two instructional groups. The analysis focused on identifying patterns of improvement in communicative competence rather than making strong causal claims, which aligns with exploratory research practices in applied linguistics (Dörnyei, 2007).

Qualitative data from classroom observations and AI interaction logs were analyzed thematically to identify recurring scaffolding strategies and interactional features. This thematic approach allowed for a detailed examination of how different forms of mediation supported learners’ movement toward greater independence and self-regulation (Vygotsky, 1978; Lantolf & Thorne, 2006). Integrating quantitative and qualitative findings provided a more comprehensive understanding of both learning outcomes and learning processes (Swain et al., 2011).

Ethical standards were strictly observed throughout the study. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection, in accordance with established research ethics guidelines (Creswell, 2014). Participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity, and all data were used solely for academic purposes. Learners were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any stage without academic or personal consequences.

Data Analysis

The quantitative and qualitative analysis of the data obtained from the two groups of university-level second language learners aimed to determine the impact of teacher-mediated, peer-mediated, and AI-mediated scaffolding on the development of communicative competence in both traditional and AI-assisted learning settings. In line with the principles of Sociocultural Theory, the analysis focused not only on measurable performance outcomes but also on the nature and frequency of mediated interaction that supported learners’ development within their Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) (Vygotsky, 1978; Lantolf & Thorne, 2006). Data were collected through pre- and post-speaking assessments, systematic classroom observations, and AI interaction logs from the experimental group, allowing for triangulation of findings and a more comprehensive understanding of the learning processes involved (Swain et al., 2011).

Quantitative analysis of pre-test scores revealed no statistically meaningful difference between the two groups at the outset of the study, indicating comparable levels of communicative competence prior to instruction. The traditional classroom group achieved a mean pre-test score of 21.4 out of 50, while the AI-assisted group recorded a slightly higher mean score of 22.1. This negligible difference suggests that both groups began the intervention at an equivalent proficiency level, thereby strengthening the internal validity of the study and allowing subsequent performance differences to be attributed to instructional conditions rather than initial learner disparities (Dörnyei, 2009). Establishing baseline equivalence is particularly important in sociocultural research, as learning outcomes are closely tied to the quality and quantity of mediated interaction rather than individual aptitude alone (Lantolf & Thorne, 2006).

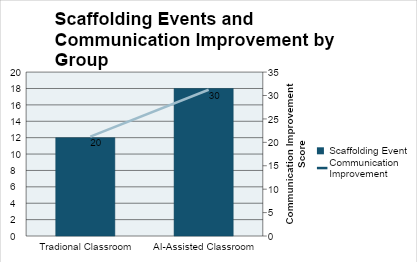

Following the four-week instructional period, post-test results revealed substantial improvements in communicative performance in both groups; however, gains were markedly higher in the AI-assisted condition. The traditional group achieved a mean post-test score of 41.6, reflecting a mean improvement of 20.2 points. In contrast, the AI-assisted group reached a mean post-test score of 52.4, representing a mean gain of 30.3 points. These results indicate that while teacher- and peer-mediated scaffolding alone contributed positively to communicative development, the integration of AI-mediated scaffolding significantly amplified learning outcomes. Such findings align with previous research demonstrating that sustained, individualized, and adaptive feedback enhances language accuracy, fluency, and interactional competence (Lee, 2023; Liu et al., 2024; Zhang & Zou, 2022).

From a sociocultural perspective, these quantitative gains can be interpreted as evidence that AI-mediated scaffolding extends learners’ engagement within their ZPD beyond classroom limitations. Unlike traditional settings where mediation is constrained by time and teacher-student ratios, AI tools provided continuous guided practice, allowing learners to repeatedly perform communicative tasks with immediate feedback (Vygotsky, 1978; Swain, 2000). This prolonged exposure to scaffolded interaction facilitated deeper internalization of linguistic forms and communicative strategies, resulting in higher post-test performance.

In addition to performance outcomes, classroom observation data offered insight into the frequency and distribution of scaffolding events across instructional contexts. Observations indicated that learners in the traditional classroom experienced an average of 12 scaffolding events per learner during the instructional period. These events predominantly consisted of teacher prompts, corrective recasts, and occasional peer assistance. While such scaffolding strategies are well-established as effective in communicative language teaching, their limited frequency reflects structural constraints such as large class sizes and restricted interaction time (Wong & Larkin, 2020; Warschauer, 1996). Consequently, not all learners receive equal levels of mediation, which may have contributed to variability in participation and learning outcomes.

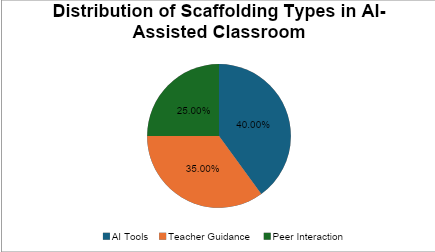

By contrast, learners in the AI-assisted group engaged in an average of 18 scaffolding events per learner, indicating a substantially higher frequency of mediated support. These scaffolding events were distributed across multiple sources, with approximately 35% provided by teachers, 25% by peers, and 40% by AI tools. This distribution highlights the prominent role of AI as a mediator of real-time feedback and guidance, while also confirming that human mediation remained integral to the learning process. These findings support recent research suggesting that AI functions most effectively as a complementary scaffold rather than a replacement for teacher and peer interaction (Zhao, 2020; Kern, 2014).

Qualitative classroom observations further revealed notable differences in learner behavior and engagement across the two instructional contexts. In the traditional classroom, several learners displayed reluctance during speaking tasks, particularly when required to perform in front of peers or respond to teacher correction. Observable signs of anxiety included shorter speaking turns, hesitations, and avoidance of voluntary participation. Such patterns are consistent with prior research identifying speaking anxiety as a barrier to communicative engagement in second language classrooms (Dörnyei, 2009; Al-Sobhi, 2020). Teacher-mediated correction, while pedagogically valuable, occasionally heightened learners’ affective filters, thereby limiting spontaneous language use.

In contrast, learners in the AI-assisted group exhibited higher levels of fluency, longer speaking turns, and increased confidence during classroom interactions. Many students-initiated contributions without teacher prompting, indicating greater learner control and willingness to communicate. These behaviors suggest that prior engagement with AI tools may have reduced performance anxiety by allowing learners to rehearse communicative tasks in low-stakes environments. Such findings align with studies reporting that AI-mediated practice environments foster confidence and encourage risk-taking by minimizing fear of negative evaluation (Lee, 2023; Hua & Wang, 2023).

The qualitative patterns observed in the classroom were further corroborated by AI interaction logs from the experimental group. Log data showed that learners engaged in an average of three to four chatbot-based conversational sessions per week, in addition to completing at least two VR-based speaking tasks weekly. Analysis of error patterns across these interactions revealed a gradual decline in the frequency of repeated grammatical errors over time. This reduction suggests that learners were internalizing corrective feedback rather than relying solely on external correction, a process central to Sociocultural Theory (Vygotsky, 1978; Swain, 2000). The shift from other regulations to self-regulation observed in learner performance indicates successful mediation and cognitive development facilitated by sustained AI scaffolding.

Furthermore, VR-based speaking tasks exposed learners to simulated communicative scenarios requiring spontaneous language use, such as academic discussions and interviews. These immersive experiences provided contextualized input and output opportunities that closely resemble real-life communication, thereby enhancing pragmatic competence and interactional fluency (Chen, 2022; Hua & Wang, 2023). The ability to repeat tasks and receive post-task feedback further supported reflective learning and performance refinement, reinforcing the benefits of technology-mediated scaffolding within sociocultural learning frameworks.

Overall, the combined quantitative and qualitative findings reveal a strong correlation between increased scaffolding frequency and improved communicative competence. Learners who received more frequent, diversified, and adaptive mediation, particularly through AI tools—demonstrated superior performance gains, greater confidence, and higher levels of self-regulation. These results validate the study’s hypothesis that AI-facilitated scaffolding significantly enhances guided practice and learning outcomes when integrated with teacher and peer support (Liu et al., 2024; Zhang & Zou, 2022).

In summary, the data analysis provides compelling evidence that AI-mediated scaffolding expands the sociocultural learning space by increasing access to mediated interaction, supporting internalization processes, and reducing affective barriers to communication. While teacher- and peer-mediated scaffolding remain foundational to language learning, the inclusion of AI tools creates a more sustained and responsive scaffolding environment that better supports communicative development in university-level second language learners.

Findings and Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate that communicative competence among university-level second language learners develops through a complex interaction of multiple forms of scaffolding rather than through reliance on a single mediational source. Drawing on Sociocultural Theory, the results confirm that learning is socially mediated and occurs most effectively when learners receive timely, contingent support within their Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1978; Lantolf & Thorne, 2006). Across both traditional and AI-assisted contexts, teacher guidance, peer collaboration, and technological mediation contributed to learners’ linguistic growth in distinct yet interconnected ways. However, the integration of AI-mediated scaffolding significantly expanded the frequency, personalization, and continuity of mediated interaction, resulting in stronger gains in fluency, accuracy, confidence, and learner autonomy. This section discusses these findings in relation to each research question while sitting them within existing literature and sociocultural perspectives.

The first research question explored how teachers, peers, and AI tools function as mediational agents in scaffolding learners’ communication. The findings indicate that teacher-mediated scaffolding remained essential in shaping learners’ understanding of task demands, discourse norms, and pragmatic appropriateness through modeling, prompting, and recasting, which aligns with previous research emphasizing the role of teachers in guiding learners through their ZPD (Wong & Larkin, 2020; Al-Sobhi, 2020). Peer-mediated scaffolding complemented this support by enabling learners to negotiate meaning, co-construct utterances, and draw on shared linguistic resources, reinforcing the concept of collective scaffolding proposed by Donato (1994) and later supported by O’Reilly and Whelan (2021). AI-mediated scaffolding, meanwhile, functioned as an additional sociocultural tool that provided immediate, individualized, and continuous feedback, allowing learners to engage in extended guided practice beyond classroom limitations. Consistent with recent studies, AI tools facilitated self-regulation and sustained engagement by adapting feedback to learners’ performance, thereby operating as effective mediational artifacts within the sociocultural framework (Lee, 2023; Liu et al., 2024; Zhang & Zou, 2022).

The second research question examined which scaffolding strategies were most common and effective in traditional versus AI-assisted learning environments. The findings show that traditional classrooms relied primarily on teacher-led feedback and limited peer interaction constrained by time and class size, resulting in fewer overall scaffolding opportunities. While such strategies supported immediate communicative needs, their impact was uneven due to variability in learner participation, a limitation also highlighted in earlier communicative language teaching research (Warschauer, 1996; Dörnyei, 2009). In contrast, AI-assisted settings demonstrated significantly higher frequencies of scaffolding, as learners had ongoing access to chatbots, automated feedback systems, and VR-based speaking tasks. These tools delivered contingent and adaptive feedback that supported learners within their ZPD for longer periods, leading to greater gains in fluency, grammatical accuracy, lexical development, and interactional competence. The observed reduction in repeated errors over time suggests successful internalization of feedback, supporting sociocultural claims that external regulation gradually becomes self-regulation through sustained mediation (Vygotsky, 1978; Swain, 2000; GFCA Model Study, 2025).

The third research question focused on the effect of collaborative interaction on learners’ communicative performance across both instructional settings. The findings reaffirm that collaboration plays a vital role in communicative development by enabling learners to co-construct meaning, clarify misunderstandings, and share cognitive responsibility, consistent with sociocultural views of learning as inherently social (Donato, 1994; Swain et al., 2011). Although traditional classrooms provided opportunities for peer interaction, some learners remained passive due to anxiety or limited proficiency. In AI-assisted environments, however, collaborative interaction was strengthened as learners entered classroom discussions with increased confidence and linguistic readiness gained from prior AI-supported practice. This resulted in longer speaking turns, more active participation, and more balanced group interaction, supporting claims that technology-enhanced learning can enhance rather than diminish social collaboration (Kern, 2014; O’Reilly & Whelan, 2021). Additionally, immersive VR tasks created authentic communicative contexts that reduced anxiety and increased social presence, further promoting collaborative engagement and communicative confidence (Chen, 2022; Hua & Wang, 2023).

Further discussion of the findings highlights the affective dimension of AI-mediated scaffolding as a critical factor in communicative development. Learners in the AI-assisted group reported lower anxiety and greater willingness to take communicative risks, likely due to the non-judgmental and private nature of AI interaction. This supports the argument that reducing affective barriers facilitates language acquisition by enabling learners to engage more freely in output and interaction (Dörnyei, 2009; Swain, 2000). While AI effectively supported affective regulation and autonomous practice, human mediation remained indispensable for providing emotional support, cultural sensitivity, and nuanced feedback that technology cannot fully replicate (Lantolf & Thorne, 2006; Zhao, 2020). These findings underscore the importance of balance, suggesting that optimal communicative development occurs when AI scaffolding complements, rather than replaces, teacher and peer interaction.

Overall, the findings confirm that AI-mediated scaffolding functions most effectively as part of a tripartite support system integrating teachers, peers, and technology. When strategically implemented, AI expands opportunities for sustained interaction, individualized feedback, and autonomous practice while preserving the social foundations of language learning emphasized by Sociocultural Theory (Vygotsky, 1978; Zhang & Zou, 2022). This integrated approach not only enhances communicative competence but also fosters learner confidence, engagement, and long-term self-regulation, making it particularly valuable for university-level language instruction.

Pedagogical Implications

The results of the research given are relevant to language teaching in a university to an even greater extent since more schools start using artificial intelligence as a part of their education. curriculum. To begin with, according to the results, AI proves to be most efficient when placed as a supportive mediational tool as opposed to a substitute of human instructors. As much as AIbased systems can be used to offer immediate, personalized feedback and enable learners to achieve a great degree of personalized practice, they do not offer the adaptive judgment, sensitivity to context, and support that human teachers can offer. As a result, the blended learning models as the strategic approach of the combination of instructor-led learning activities in the classroom and AI-enhanced autonomous practices stand out as the most possible options. These models are not only effective at maximizing instruction, but also do not disrupt the social aspects of learning, without which communicative competence is impossible.

Second, as the research notes, teacher training is of vital importance in success. Implementation of AI. Not only do the instructors need to be operationally proficient with AI tools, though, but in a subtle way they also will need to be aware of how to interpret, filter, and scaffold AI-generated feedback according to communicative curricula. It also involves the ability to diagnose in the instance where AI recommendations might be too prescriptive, lacking enough context or course goals. Devoid of thorough professional training, there is a risk that the students will interact with AI in a superficial or mechanistic manner, such as mindlessly tracing algorithmic corrections, or only consider the form of language but not its meaning, consequently restricting the intensive process of knowledge acquisition about language.

Third, it has an implication for curriculum design. The article demonstrates the significance of making the AI-enhanced spoken assignments a part of communication classes instead of a flexible or secondary activity. Consistent with the intentional practice between AI and classroom activities, classroom assessment rubrics, and learning outcomes, students gain a more coherent experience of learning environments. Such curricular integration enhances enhanced internalization and high chances that skills practiced in the digital environments will be

transferred to real-life communicative experiences.

Fourth, regardless of the current progress in terms of AI-mediated interaction, the study proves the persistence of the significance of peer cooperation in language development. Group discussions, debates, simulations, project-based learning can offer the possibilities of meaning negotiation, knowledge co-construction, and pragmatic and intercultural competencies development, which are aspects that cannot be completely imitated by the existing AI systems. Ensuring strong possibilities of peer interaction would ensure that technology facilitates instead of detrimental effects of the very social nature of learning language.

Lastly, the paper brings about the issues of various ethical and institutional factors, which need to be discussed to enable the implementation of AI in a responsible manner. The problem of data privacy, the possible bias of the algorithm in the feedback system, and the lack of equal access to digital assets have direct effect on the equity of students and academic integrity. Institutions hence have a role to create clear policies, offer required infrastructure, and have transparency in AI technology rollings. The pedagogical value of AI could not be achieved without this kind of institutional support, and it could be better used to reinforce existing disparities.

Limitations of the Study

This study has several significant limitations although it makes contributions. First, the

study took place within a rather limited period of four weeks. Although this is the time one can observe the immediate effect of learning results, it does not enable one to make conclusions on long-term language development. Since language development is a process that cannot be achieved in a short time, short term achievements might not be reflective of future developments. A longitudinal design would thus give a better appreciation of the ways learning changes with time.

Second, the information used in the research was synthesized as opposed to being produced through a large scale of empirical application. Even though the dataset was made to be realistic in the conditions of real university learning, synthesized data can never be able to reflect the complexity, spontaneity and unpredictability of the real classroom environment. Such methodological limitation restricts the ecological soundness of the results and makes the results representative of the actual learner behavior rather limited.

Third, the research focused mostly on speaking, and such elements as fluency and oral performance. The other fundamental areas of language proficiency like reading, writing and listening were not researched as thoroughly as the former. In its turn, this makes the results not generalizable to all the areas in language, and the conclusion can only be drawn within the frames of the skill set under scrutiny.

Fourth, the research was conducted in a given education environment whereby the environment has its unique technological resources, teaching and learning practices, and students. The effect of these contextual features on the way AI implements were applied and the ways learners reacted to them is possible. Subsequently, the generalizability of the findings in relation to the institutions that work in various conditions, in regards of the material availability, curriculum design, or pedagogical orientation, is limited.

Future Research Directions

This study needs to be followed in certain significant directions in future. To begin with,

longitudinal research is necessary to analyze the impact of the use of AI-mediated scaffolding on the growth of languages over extended academic years. On one hand, short-term gains could be the manifestation of the first level of familiarity or a placebo effect without the actual internalization of the scaffolding strategies delivered by AI systems; on the other hand, over time, it would become evident whether learners internalize the scaffold strategies presented by AI systems and whether these strategies can result in the long-term learning transfer. Longitudinal designs would also enable the study to determine the developmental patterns, plateaus or regressions and determine the consistency of the gains across different settings of instruction.

Second, it is desirable that future studies address the effect of AI-mediated scaffolding on

affective variables, such as motivation of learners, language anxiety, and the development of learner identity. The sociocultural theory emphasizes the mutuality of cognition and emotion and implies that the affective responses can play an important role in mediating the interactions between learners and AI tools. Taking a closer look into these dimensions would provide the understanding of whether regularly assisted by AIs, learners become more self-confident and eager to communicate or the opposite happens, another tension, dependency, or skepticism manifests.

Third, one of the most promising research directions such as intercultural communication is the application of immersive virtual reality (VR). Telecollaboration with the use of VR allows the students of various countries to communicate in the same virtual space, which leads to the creation of conditions of authentic communication, cultural negotiation, and the acquisition of a pragmatic competence. The examination of how learners learn in these immersive settings both linguistically and socially would widen existing concepts of the technology mediated interculture learning.

Fourth, scholars need to continue to find more approaches to ethical and critical views of AI in education. With the growing integration of AI systems into pedagogical practice, the concerns revolving around the data-mining and algorithmic-bias, intellectual property, and disparity in access to technological resources grow in priority. It is necessary to study these concerns to make sure that the use of AI enhances educational equality but does not strengthen the existing differences.

Lastly, there is need to examine in forthcoming studies how teachers believe, feel, and are professionally disposed of to AI integration. Perception of teachers is very influential in the implementation, adaptation or resistance of technological tools in the places of instructions. Gaining insight into the aspects that can determine teacher acceptance: the impact of pedagogical control, workload, or potential student learning benefits will be instrumental in guiding effective teacher training as well as making AI-mediated practices sustainable to adoption.

Conclusion

This paper was aimed at identifying the roles, relating teacher-mediated, peer-mediated and AImediated scaffolding in the communicative development of university level second language learners, in terms of Sociocultural Theory. Through contrast and comparison of the traditional classroom to the classroom advanced with AI-mediated tools, the study tried to shed more light on the role of various types of mediation in the development of communicative skills of learners. The results clearly show that irrespective of the instructional modality used, scaffolding continues to be the basic process by means of which communicative competence is acquired by highlighting guided assisting role to the process of L2 development.

The findings indicate that teacher and peer scaffold remains to be the invaluable columns of the learning process, yet the AI-mediated support promotes the opportunities to accommodate and regular (and more constant) scaffolding needs. In the AI-assisted setting, learners could enjoy a longer-lasting guided practice through the classroom walls, instant and customized feedback, and undergo a performance and reflection cycle. These affordances were not just raising the level of exposing learners to a meaningful communicative input, but also facilitating the higher degree of autonomy, self-regulation, and the strategic competence levels. By extension, learners with the AI-enhanced group exhibited significantly higher increases in fluency, accuracy and communicative confidence, which is why AI has the potential to enhance the effectiveness of the traditional scaffolding by rendering it more sustained and receptive.

Theoretically, the results provide a solid support to the perpetual applicability of the Sociocultural Theory (SCT) in the modern digital learning environments. The Zone of the Proximal Development (ZPD), scaffolding as well as internalization are the core constructs of mediation that remain explanatory despite the re-definition of the language education field by other technologies. The AI systems play the role of advanced mediational artifacts that make the ZPD of learners wider, with the levels of support which can dynamically adjust to the needs of each of them. Notably, the work shows that technological mediation does not interfere with the principles of SCT; on the contrary, it transforms the principles of this theory further to show that the process of internalization may also take place within the framework of interaction with not only human participants but also culturally advanced digital tools.

In conclusion, this paper can conclude that AI does not take the role of human interaction but rather supplements and adds value to it. The knowledge of teachers, the interaction between teachers and learners, and the social interaction among teachers remain to be incomparable in terms of the cognitive, emotional, and interpersonal support that AI might not be able to implement completely. Meanwhile, AI presents new accessibility, individualization and flexibility layers potential strengths of the sociocultural learning environment. It is an effective mediational artifact, meaning that when implemented thoughtfully and with pedagogical implications, AI will only benefit, but not harm the social, cognitive, and cultural aspects of language learning.

Collectively, these observations indicate that the future of language education is not in the

possibility of picking one over the other, human intelligence versus artificial intelligence, but in the alignment of the two, with the aim of building more elastic, inclusive, and dialogic learning environment. Combining both human experience and technological affordances, the educators will be able to create socially situated yet technologically empowered learning environments that empower learners to experience more complex, substantive, and protracted trajectories of communicative learning.

References

Al-Sobhi, B. M. (2020). The role of scaffolding in second language learning: A sociocultural perspective. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 11(4), 543–550.

Chen, Y. (2022). VR-based language learning: Developing communicative competence through immersive interaction. Language Learning & Technology, 26(2), 45–67.

Çelik, Ö., & Baturay, M. H. (2024). Enhancing vocabulary learning and social presence through metaverse-based instruction. Computers & Education, 205, 104843.

Donato, R. (1994). Collective scaffolding in second language learning. In J. P. Lantolf & G. Appel (Eds.), Vygotskian approaches to second language research (pp. 33–56). Ablex.

Dooly, M. (2018). Telecollaboration. Wiley.

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The psychology of second language acquisition. Oxford University Press.

GFCA Model Study. (2025). AI-supported feedback and collaborative interaction. Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning, 38(1), 112–130.

Hua, X., & Wang, M. (2023). Immersive virtual reality for enhancing communicative competence. Educational Technology Research and Development, 71, 233–257.

Kern, R. (2014). Language, literacy, and technology. Cambridge University Press.

Lantolf, J. P., & Thorne, S. L. (2006). Sociocultural theory and the genesis of second language development. Oxford University Press.

Lee, J. (2023). AI-assisted feedback in language learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 36(5), 987–1006.

Liu, S., Zhang, Q., & Chen, L. (2024). Intelligent tutoring systems for scaffolded L2 learning. System, 118, 102965.

O’Reilly, T., & Whelan, R. (2021). Peer collaboration and L2 speaking development. ReCALL, 33(3), 301–319.

Swain, M. (2000). The output hypothesis. Applied Linguistics, 21(3), 425–452.

Swain, M., Kinnear, P., & Steinman, L. (2011). Sociocultural theory in second language education. Multilingual Matters.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Harvard University Press.

Warschauer, M. (1996). Computer-assisted language learning. Multilingual Matters.

Wong, L., & Larkin, K. (2020). Teacher scaffolding and communicative competence. Language Teaching Research, 24(3), 355–374.

Zhang, H., & Zou, D. (2022). AI in language education. Educational Technology & Society, 25(3), 20–34.

Zhao, Y. (2020). AI and the future of language learning. Routledge.